Student Work, "Comics in the Archive"

In the spring 2019 “Comics in the Archive” course, undergraduate students contributed to a digital finding aid about the Stephen Cooper comic book collection and then analyzed the content they created, developing visualizations and other visual analyses using digital platforms. Students analyzed a variety of visual and historical topics, including: the prominence and comparison of genres; the relationship between publishers and genres; color composition of individual characters; and text analysis that can signal differences in genre.

A sample of student work is included here. All student work is posted with their permission and rights remain with the students.

Sally Boniecki

In this snapshot of comics from April 1956, certain trends indicate the mindset and methods of artists of the day. Whether the decision be made by a designer, inker, or colorist, palette trends are evident. Initially, my endeavor began with an assumption that colors would reveal a crutch in visual language such as associating red with antagonists in the midst of the Red Scare. However, the student led to a more complex conclusion with a[n] added divide in gender and heavy reliance on real life fashion trends. Only a few tropes tipped the percentages in any particular direction.

After all data was gathered and broken down, the strongest trend appeared within all female characters no matter their alignment. Red and black were incredibly popular, with white following closely behind. White appeared most often as a blouse or a white collar. This general style and color trend was fairly popular with young women of the 1950s, so the general reliance on everyday clothing amplified the lack of deviation. Ease of printing on cheap machines may have also contributed to the trend, as red and black were reliably consistent and white used no ink at all. The lack of women working in the industry makes the strong trend toward similar outfits unsurprising.

Male characters deviated more in design when separated by alignment. Protagonists were clearly a majority working and middle class, so there was a clear trend towards blue, whether it be from business suits, uniforms, or supersuits. Brown followed for the same tactical, practical reason. Black and white also appeared incredibly often in the form of collared shirts and ties. Yellow also ranked fairly high as a secondary color, and upon further inspection, most instances occurred in a black and yellow scheme or a representation of gold accents. For the most part, male protagonist costumes were mellow and realistic.

Overall, these trends reveal more about 1950s fashion, the 1956 comic industry, and modern visual language than it does conscious color theory in the original production of the Cooper Collection comics. As an idealized reflection of the fashion of the day, these comics present a comprehensive picture of the story writing values influenced by the code; safe genres had pretty strong color trends due to the common appearance [of] suits and uniforms, and shortcuts or methods used by the artists bled over into modern visual language via long-lasting characters. Purple remains associated with villains after characters such as the Penguin continued to appear in comics and media to this day, usually with some sort of purple accent. Blue, as a color on the American flag and protagonists alike, remains a “heroic” color for costumes representing “truth, justice, and the American way.” As far as the industry itself goes, the strong trends/lack of true deviation continues thanks to the majority male writers, designers, and artists. As a turning point in comics leading into the Silver Age, this collection and the data from my investigation gives a bit of insight to how certain artistic trends spread in the following decades.

Andrew Lefurge

The following is an academic analysis of the reproduction and modern availability of legacy Comics from the Cooper Comics Collection. The analysis places a particular focus on the forms in which these comics have been made available to modern audiences, as well as what is and is not available. This analysis hopes to show how modern tastes and market forces have shaped public perception of the history of comics, and may not serve as an accurate representation of the medium's legacy.

Using a number of online resources, I assessed the availability of every comic featured in our corpus. My analysis focused on comics sold as part of collected editions as well as single issues that are available digitaly on online storefronts. The results of this analysis showed that only 23% of the series in the collection were availbale and only 16% of the specific issues in our collection were available.

Of the comics that are available on digital comics platforms, two separate approaches have emerged for how to treat the materials. The first method, that can be seen with this Popeye cover, is more of a remastering than a complete recoloring. In this case, it is apparent that IDW has opted to modify a scan of the original comic rather than digitally reproduce it. Here, IDW has likely used digital tools such as Photoshop to clean up and regrade a scan of the original comic. While this technique produces a more pleasing result for a screen based reading experience, it does negatively affect the overall contrast and accuracy of the colors. The second approach for treating the materials involves artists completely digitally re-inking comics.

View the finalized project page and full analysis: https://mikrowelle.github.io/cooper-comics-final/

Jake Sikorski

This research discovers which market the comics of a specific time period were tailored to through textual analysis, assessing the difficulty of the story to an English reader. For this research, all problematic genres—detective/mystery, romance, and horror/suspense—on storefronts during the month of April 1956 were selected.

I used the Flesch Reading Ease and Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Test to determine the readability scores of individual stories in a sample of books in the Cooper Comics Collection. The two different tests are similar, but they place a different emphasis on sentence structure and utilize different weights.

The Flesch Reading Ease score is a scale, typically in the range from zero to a hundred and carries an inverse proportion. A higher score indicates a passage is easier to read. The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Test calculates at what minimum grade level the passage is most likely to be understood by. While not equal, they both draw similar conclusions and can be used to complement each other.

In total, across twenty-three comic books there were one hundred and one individual stories. The following graph is a histogram visualization of the Flesch reading score of the individual stories.

The readability scores, demonstrated by the red line in the graph, were organized into collections. There are no scores in the low end of the range. The scores are concentrated in the high eighties, breaking in the low nineties before another concentration in the scores in the upper nineties.

The light green bars indicate the spread of the data. The Flesch Reading Ease score had a mean of 89.932 and a standard deviation of 5.519. The low standard deviation and the higher mean range support the data’s observation of scores clustered in the upper bound of the Flesch score range.

While the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level and the Flesch readability score differ in weight, they take into consideration the same metric. In this instance, the data from the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level agrees with the Flesch Reading Ease scores. The mean for the grade levels required to comprehend the story with minimal difficulty is 3.189. There are no data points that are outside this range for this dataset.

Drawing upon the Flesch-Kincaid grade level and the Flesch reading ease score, it is apparent that the comics in this corpus were written in to be readable by a young audience, such as elementary and middle school aged children. No definite conclusion can be drawn if this was done deliberately, as it is suggested the scores these stories fall in are equivalent to the level of English spoken in normal conversation. The stories in these comics are dominated by conversations between two individuals, so it would make logical sense that the text is written in conversational English. However, it would not be baseless to claim that these comics were addressed to children, as qualitative observation shows minimal sophistication in vocabulary. The general conclusion that can be drawn from this research is that the the text within these comics could be understood easily by elementary or middle school aged children. This audience may be intentional, or it may be because conversational English tends to hover around that reading level. A deeper linguistic analysis could further prove, disprove, or complicate this theory, since a readability test focuses on surface features.

Tyler Hollinger

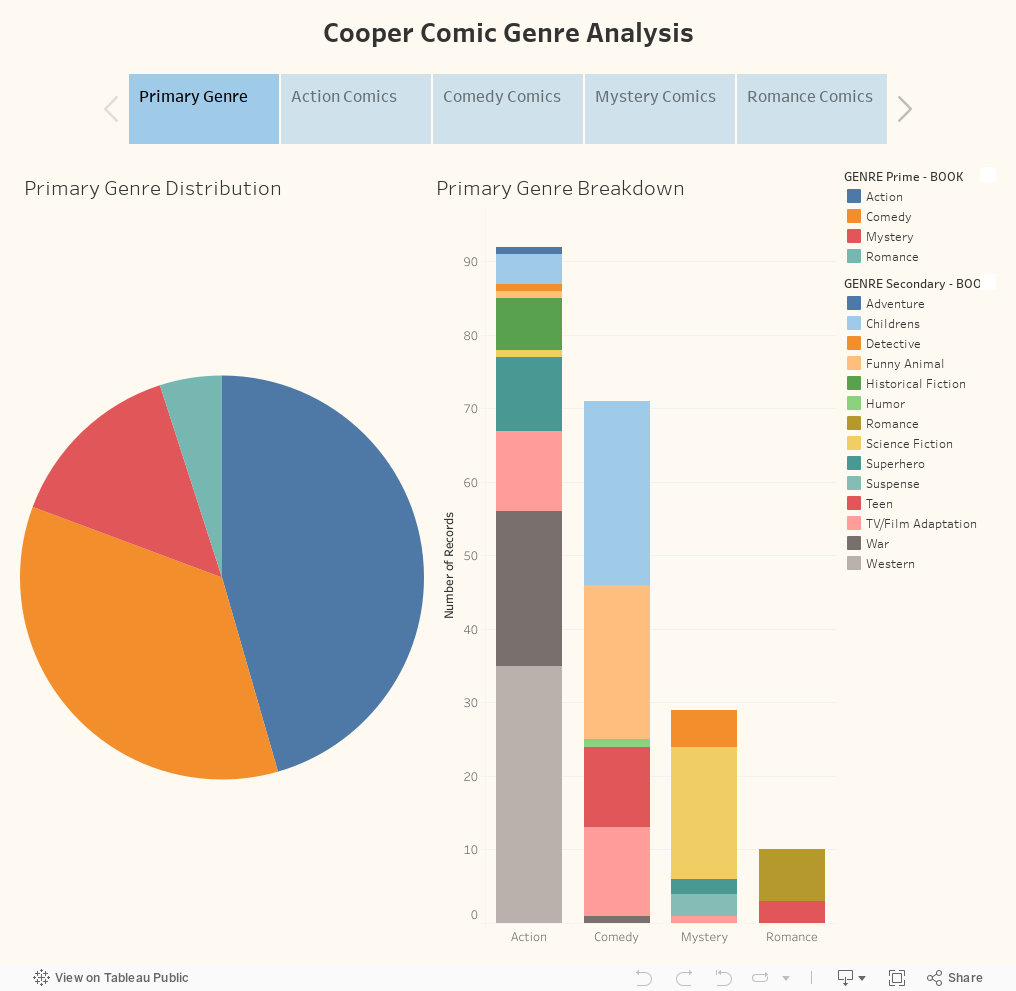

Action books:

Of the Action based comics, the majority of them are either War or Western comics. This is important as War comics in particular seemed to have an amount of leniency offered to them by the Comic Code Authority in that they were allowed to kill people so long as it was done with explosions. It seems the reason for the prominence of War and Western comics, and the leniency towards them despite their violence, is that inherent to both genres are elements of nationalistic propaganda supporting American. The Americans were the victors of most of the portrayed conflicts in the War-focused comics, or those forces that were allied with the Americans won. The few instances of comics about the Civil war even went so far as to have both sides walk away with their dignity rather than one clearly dominating the other. The Western comics followed suit in showing the goodness of old fashion U.S.A. Of course, there were criminals, but stories of the people banding together and noble heroes saving the town drew focus to a very positive version of U.S. history. The Western comics served in large part to draw away the focus of the world from some the terrible things that the U.S. was responsible for and the horrible acts of its past to highlight a sense of a noble American spirit that all true patriots in the U.S.A. possessed.

Comedy books:

The fact that the majority of the Comedy comics were focused towards a younger audience of children helps to enforce the idea of Comedy as a safe fall back for comics to rely on during the time of turmoil in the industry that spawned the Comics Code Authority. None of the humor is particularly controversial, nor thought provoking (with the notable exception of MAD and its non-conformity to the Comics Code). These comics are a clear attempt to go back towards the idea of comics as simply a dedicated publication for funnies outside of the newspapers.

Mystery books:

Most of the Mystery comics were fantastic stories that contained some form of moral at the end. The format that they followed was similar to a folk tale, though usually with advanced technology and aliens replacing what would have otherwise been magic and fairies. While some detective styled comic books remained, they did not cover particularly heinous crimes.

Romance books:

The Romance comics had very little in terms of any form of creative liberties. Not only were they the single smallest grouping of comic books, but they also had a virtually homogeneous story line set up around a woman or man attempting to get married and start a model All-American family; the husband works, the wife tends to the house, and they have a few children. There was little deviation from this as a motive, which meant that each story played out very predictably. This predictability might have in turn hurt sales and caused the smaller number of comics, but I believe it is far more likely that the Comic Code Authority actually ended up cracking down much harder on Romance comics than any other genre of comic book. One of the major points of controversy besides violence that brought about the Comic Code Authorities creation was the potentially sexually explicit nature of some of the comic books.

Though much of what is in the narrative of comic book history will not be changed by the existence of this collection and the data I have aggregated from it, there are some key points to the history of the industry that can be amended. The action and general violence, while censored to a degree, did not disappear by any means from comic books with the introduction of the Comics Code. It, instead, adapted to the times that it found itself in and rebranded the violence as patriotism through War and Western comic books. Similarly, and likely due to this shift in large part, Action comics were not the most effected comic books by the Comic Code Authority. From the data collected from the Cooper Comic Collection, it would seem that Romance comics were instead the most effected by the censorship that was self-imposed on the industry. Not even the Mystery driven comics fared as poorly as the Romance comics, and they lost almost the entirety of the horror genre that was said to be so prevalent before the introduction of the Comics Code. This shift in comics suggests a degree of conscious rebranding towards what the government and public found most acceptable at the time: a large amount of patriotism due to the Cold War and the looming Red Threat, along with cheerful meaningless content to distract from the sense of impending apocalypse that accompanied this period within the Cold War. The idea of rebranding similarly fits with how the treatment of Superman and how he became a mascot for America during this time period as well. The Comics Code Authority undoubtedly censored the content of comics, but due to the gaps in their censorship (such as the deaths in war comics) it would appear that there was an effort to align comics very closely with the ideals of the U.S.A. to rehabilitate the concept of comic books in the eyes of the general adult populous. They did not want to be the exciting picture story books anymore, but rather a purveyor of American patriotism to the youths of the Cold War.